The Heroic Martyr for the Truth

Act 1

Foreword

On October 22, 1422, Charles VI died, bequeathing, by the Treaty of Troyes, his kingdom with the hand of his daughter to Henry V, King of England.

In the century since war devastated our country, never has our independence been so threatened.

Masters of Guyenne, united on one side with the Duke of Burgundy, on the other supported by the Duke of Brittany, the English held the north and center of France, as far as the Loire.

Orléans, besieged, presented a final obstacle to their march towards the south; but the city without help was going to succumb.

The Dauphin Charles VII had taken refuge in Bourges: a sad king, without an army, without money, without energy. A few courtiers were still competing for the last favors of this sinking monarchy, but none of them was capable of defending it, and, across the hungry countryside, the remnants of the royal army, bands of road warriors from all sources, reduced and demoralized by their recent defeats at Cravant and Verneuil, fell back incapable of a new effort.

Everything was lacking: men, resources, even the will to resist. Charles VI, despairing of his cause, thought of fleeing to Dauphiné, perhaps even beyond the mountains, to Castile, abandoning his kingdom, his rights, and his duties.

After the madness of Charles VI, the indolence of the Dauphin, and the selfishness and incapacity of the nobility, had completed the ruin of the country, our very race was going to lose its nationality.

Then, on the borders of Lorraine, in a remote village, a little peasant girl stood up. Moved with pity by the miseries of the poor people of France, she had felt in the depths of her heart the first thrill of the homeland. With her weak hand, she picked up the great sword of vanquished France, and, with her frail chest making a bulwark against so much distress, she drew from the energy of her faith the strength to raise up the lost courage and to uproot our country to the victorious English.

“I come from my Lord God,” she said, “to save the kingdom of France.”

And she added: “This is what I was born for.”

It is for this, in fact, that she was born, the holy girl; this is also why, delivered cowardly to her enemies, she died in the horror of the cruelest torture, abandoned by the King she had crowned and the people she had saved.

Open, my dear children, this book with devotion in memory of this humble peasant woman who is the patroness of France, who is the saint of the homeland as she was its martyr. His story will tell you that to win, you must have faith in victory. Remember this, the day when the country will need all your courage.

Scene 1

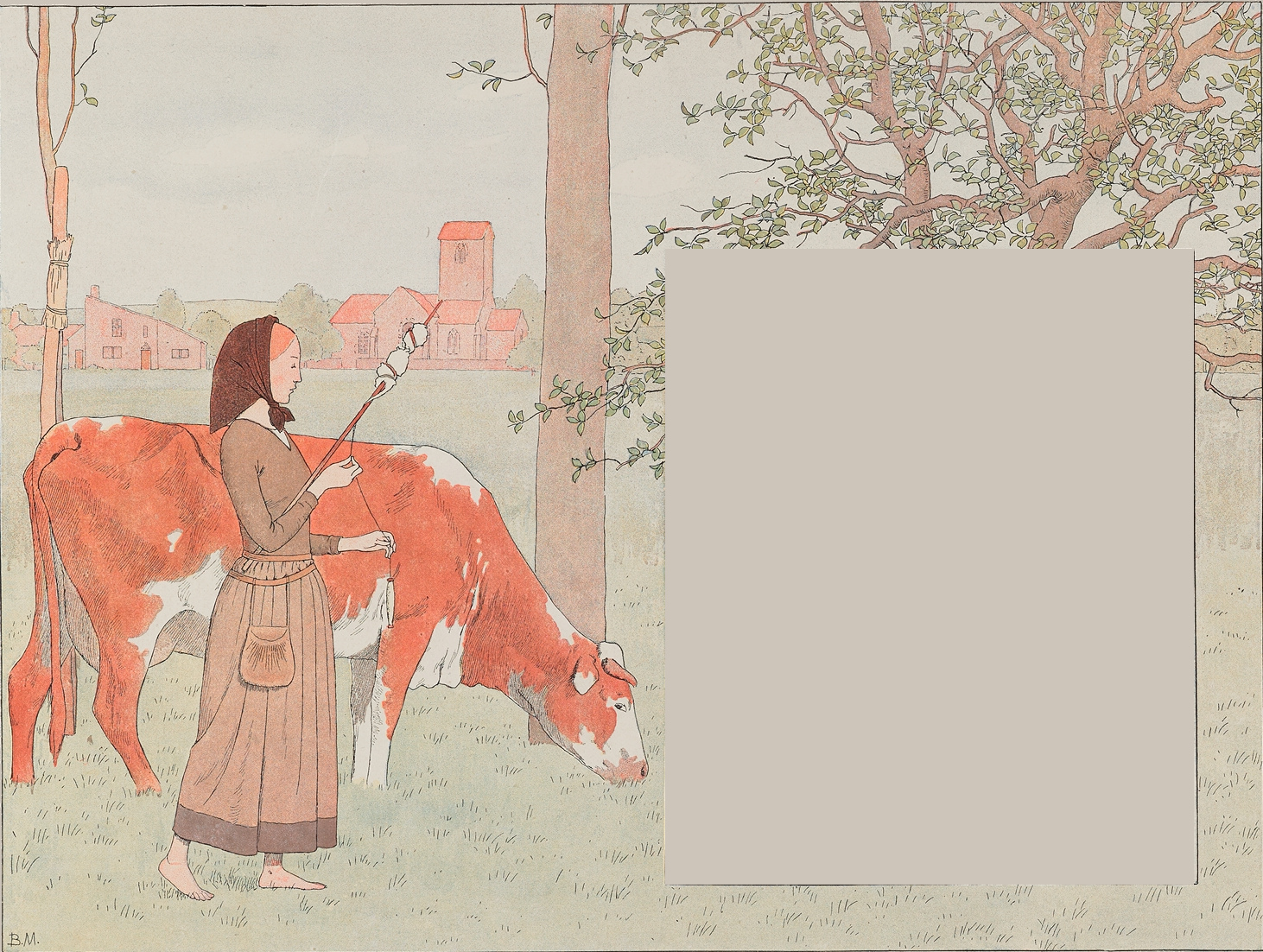

Joan was born on January 6, 1412, in Domrémy, a small village in Lorraine, dependent on the bailiwick of Chaumont, which came under the crown of France.

Her father's name was Jacques d'Arc, and her mother was Isabelle Romée; they were honest people, simple laborers living from their work.

Joan was raised with her brothers and her sister in a small house that can still be seen in Domrémy, so close to the church that its garden touches the cemetery.

The child grows up there under the eye of God.

She was sweet, simple, and straight. Everyone loved her because they knew she was charitable and the best girl in her village. Diligent at work, she helped her family in their tasks, during the day leading the animals to pasture, or taking part in her father's hard work, in the evening spending time with her mother and assisting her in the care of the household.

She loved God and prayed to Him often.

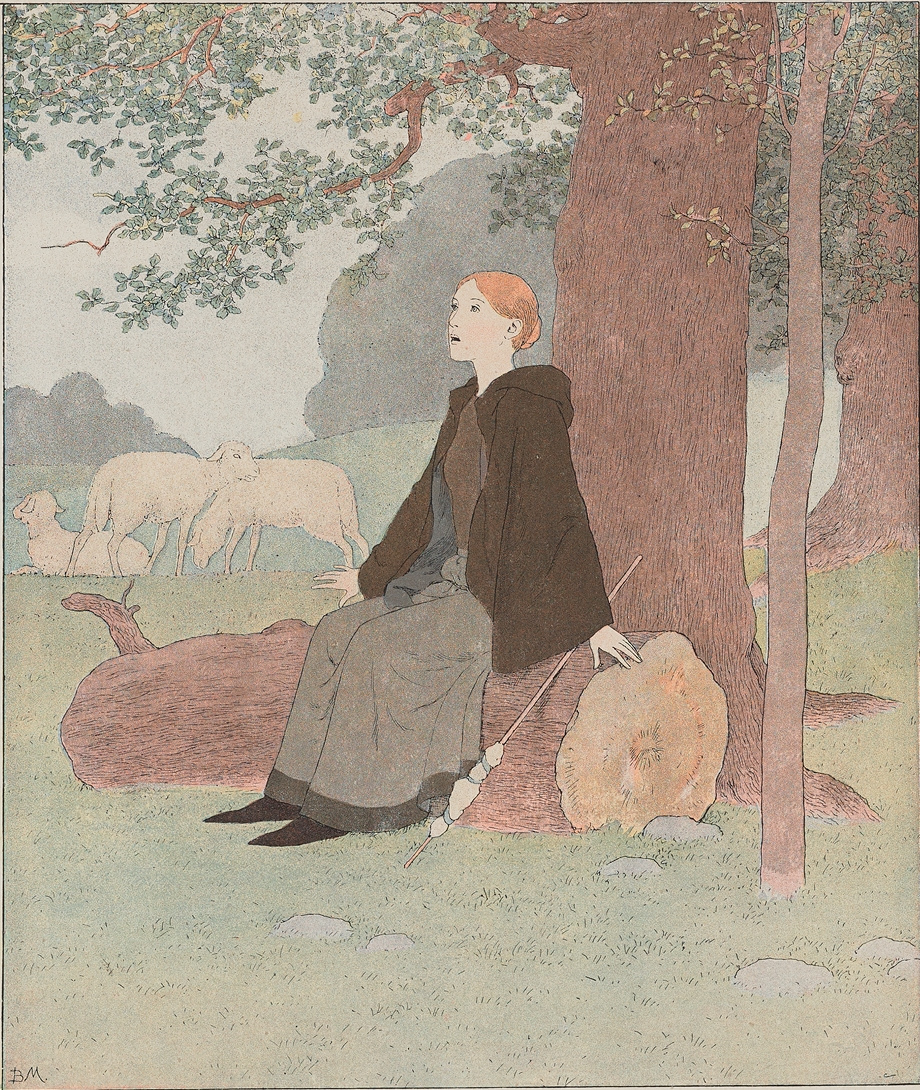

Scene 2

One summer day, when she was thirteen years old, as it was noon, she heard a voice in her father's garden; a great light broke out, and the archangel Saint Michael appeared to her. He told her to be good and to attend church. Then, telling her of the great pity that was in the kingdom of France, he announced to her that she would go to the aid of the Dauphin and that she would take him to Reims for coronation.

"Sir, I am only a poor girl, I cannot ride or lead men-at-arms."

"God will help you", replied the archangel.

And the upset child remained crying.

Scene 3

From that day on, Joan's piety became even more ardent; The child willingly separated herself from her companions to meditate, and heavenly voices were heard, speaking to her of her mission. They were, she said, the voices of her Saints. Often these voices were accompanied by visions; Saint Catherine and Saint Marguerite appeared to her.

“I saw them with the eyes of my body,” she later told her judges, “and when they left me I cried; I would have liked them to take me with them.”

The child grew up, her spirit exalted by his visions and keeping deep in her heart the secret of her celestial conversations. No one suspected what was happening inside her, not even the priest who heard her confession.

At the beginning of the year 1428, Joan was eighteen years old, and the voices became more urgent.

“The danger is great, Joan has to leave to help the King and save the kingdom.”

Her Saints ordered her to go find the Lord of Baudricourt, Lord of Vaucouleurs, and to ask him for an escort who would take her to the Dauphin.

Not daring to share her plan with her parents, Joan went to Burey to find her uncle Laxart and begged him to take her to Vaucouleurs. The ardor of her prayer shook the timidity of the fearful peasant; he promised to accompany her.

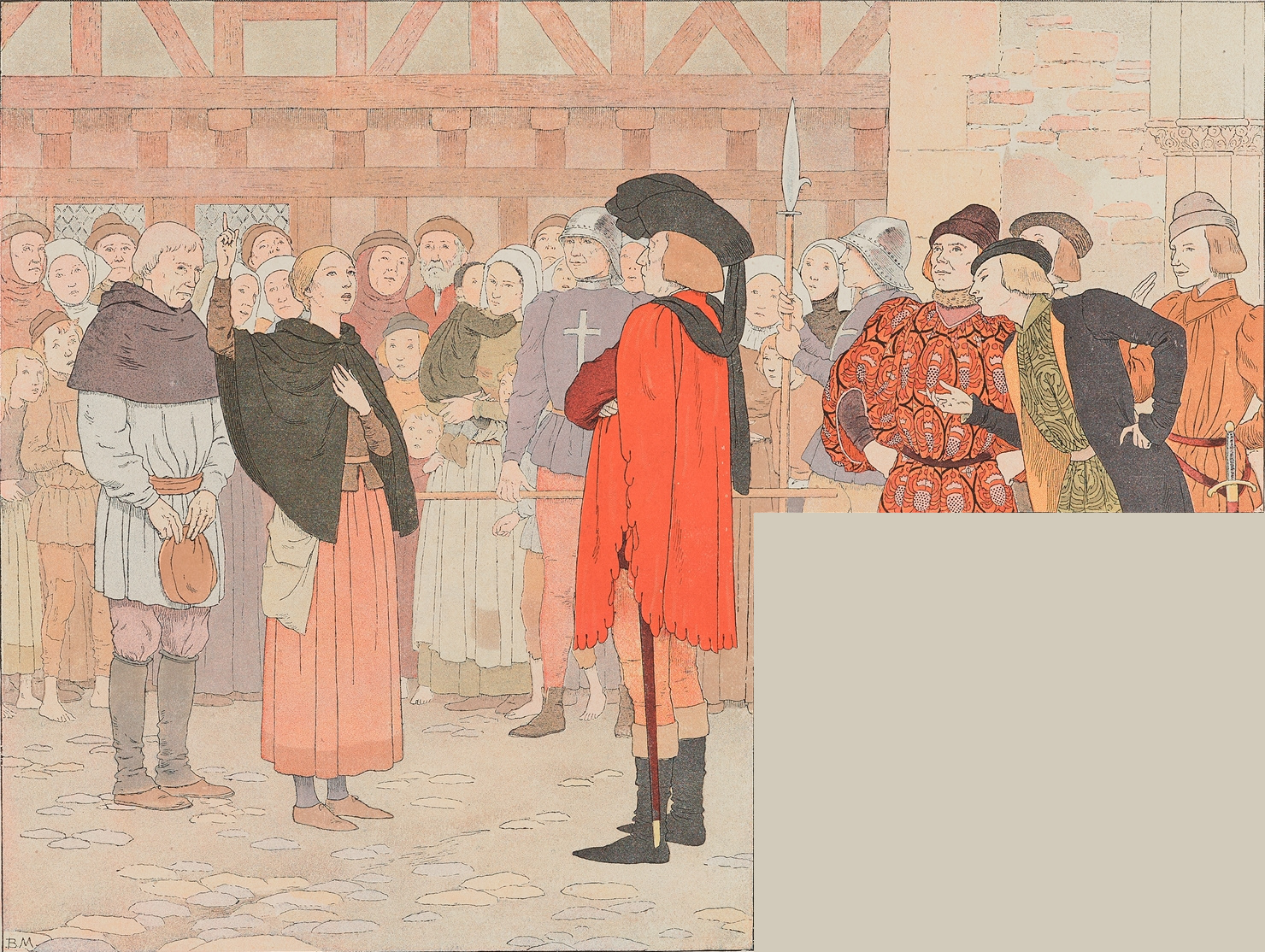

Scene 4

Baudricourt's reception was brutal. Joan told him "that a message came from God, that God would command the Dauphin to behave well because the Lord would give him help before the middle of Lent"; she added "that God wanted the Dauphin to become King; that he would do so in spite of his enemies, and that she herself would lead him to the coronation".

"This girl is crazy, said Baudricourt, let’s take her back to her father to give her a good pair of slaps."

Joan returned to Domrémy. But pressed again by her voices, she returned to Vaucouleurs and saw the Lord of Baudricourt again without obtaining a better welcome.

Scene 5

But this time she stayed in Vaucouleurs.

vSoon the only noise in the country was about this young girl, who was going around saying loudly that she would save the kingdom, that she must be taken to the Dauphin, that God wanted it.

“I will go,” she said, “even if I wear out my legs up to my knees.”

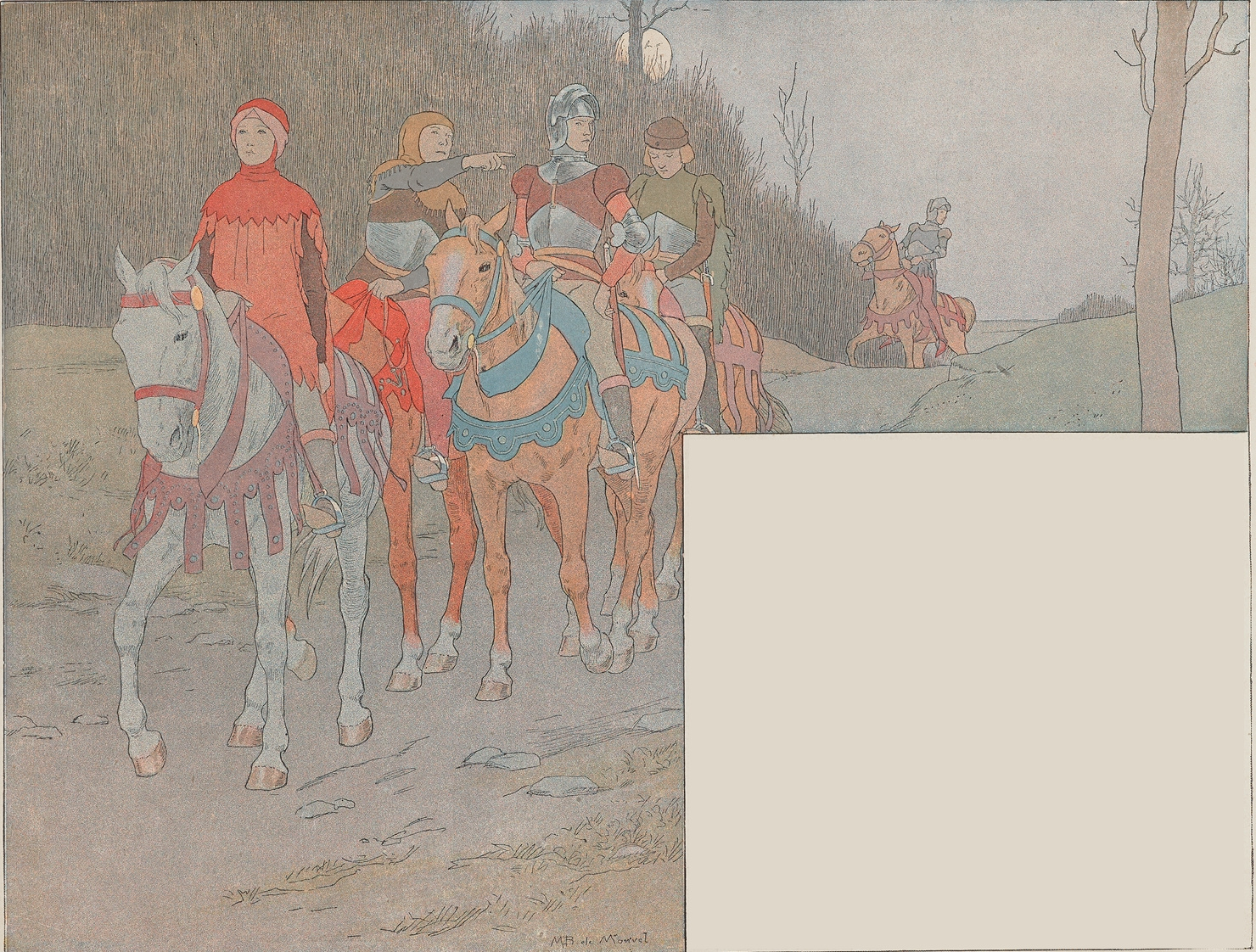

The people, of simple hearts, moved by her faith, believed in her. A squire, Jean de Metz, won by the confidence of the crowd, offered to take her to Chinon, where Charles VII was. The poor people, uniting their miseries, joined together to clothe and arm the little peasant girl. They bought her a horse, and on the appointed day she set out with her weak escort.

“Go. And come what may!” Baudricourt threw her.

"God bless you!" cried the poor people, and the women wept as they saw her go away.

Scene 6

Chinon was far away and the journey perilous. The English and Burgundian partisans held the country, and the small troop was obliged to pass through certain bridges which the enemy occupied. You had to walk at night and hide during the day. Joan's companions, frightened, talked of returning to Vaucouleurs.

"Fear nothing, she told them, God gives me my way, my brothers in paradise tell me what I have to do."

On the twelfth day, Joan arrived in Chinon with her companions. From the hamlet of Saint Catherine, she had sent a letter to the King announcing her arrival.

The court of Charles VII was far from unanimous on the reception which should be given to her. La Trémouille, the favorite of the day, jealous of the ascendancy she had gained over his master, was determined to remove any influence capable of tearing Charles from his torpor. For two days, the council discussed whether the Dauphin would receive the inspired young woman.

Scene 7

At that moment, news arrived from Orléans so disturbing that Joan's supporters managed to ensure that this supreme chance of salvation was not ruled out. In the evening, by the light of fifty torches, in the great hall of the castle, where all the lords of the court crowded together, Joan was introduced. She had never seen the King. Charles VII, in order not to attract her attention, wore a less luxurious costume than those of his courtiers. At first glance, she distinguished him among all, and kneeling before him:

“God bless you, kind Dauphin!” she says

"I am not the King," he replied, “this is the King.” And he designated a lord for him.

"You are, kind prince, and no other; the King of Heaven sends you word through me that you will be crowned."

And approaching the object of her mission, she told him that God had sent her to help and succor; she asked that he give her an army, promising to lift the siege of Orléans and take him to Reims.

The Dauphin remained hesitant. This girl could be a witch. He sent her to Poitiers to submit to the examination of doctors and ecclesiastics.

Scene 8

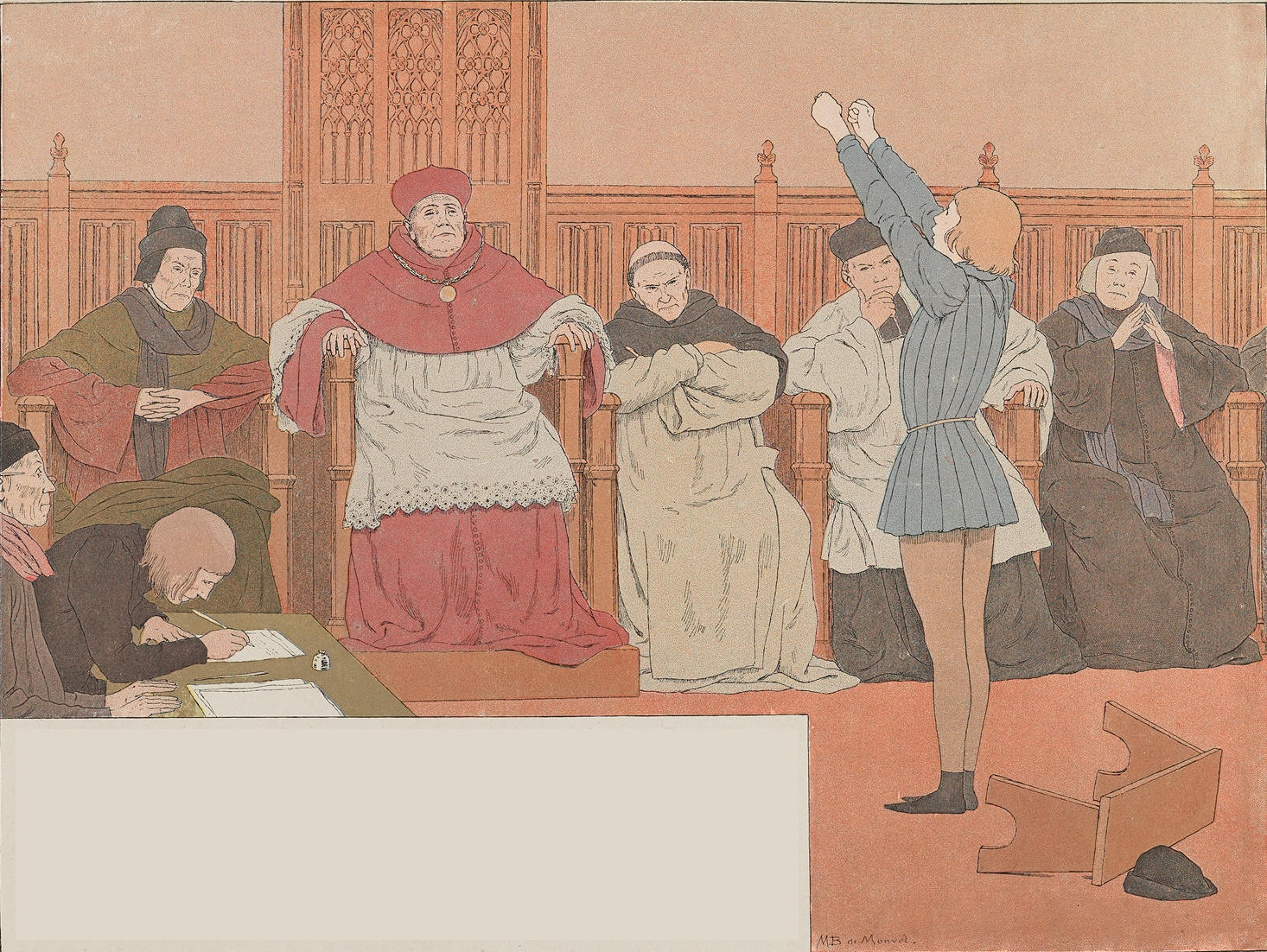

For three weeks she was tortured with insidious questions.

“There is more in God's book than in yours,” she replied; “I know neither A nor B, but I come from the King of Heaven.”

As it was objected to her that God, to deliver France, did not need armed men, she stood up suddenly:

“The men will fight, God will give the victory.”

There as in Vaucouleurs, the people declared themselves in her favor, they considered her holy and inspired. The doctors and the powerful had to give in to the enthusiasm of the crowd.

Scene 9

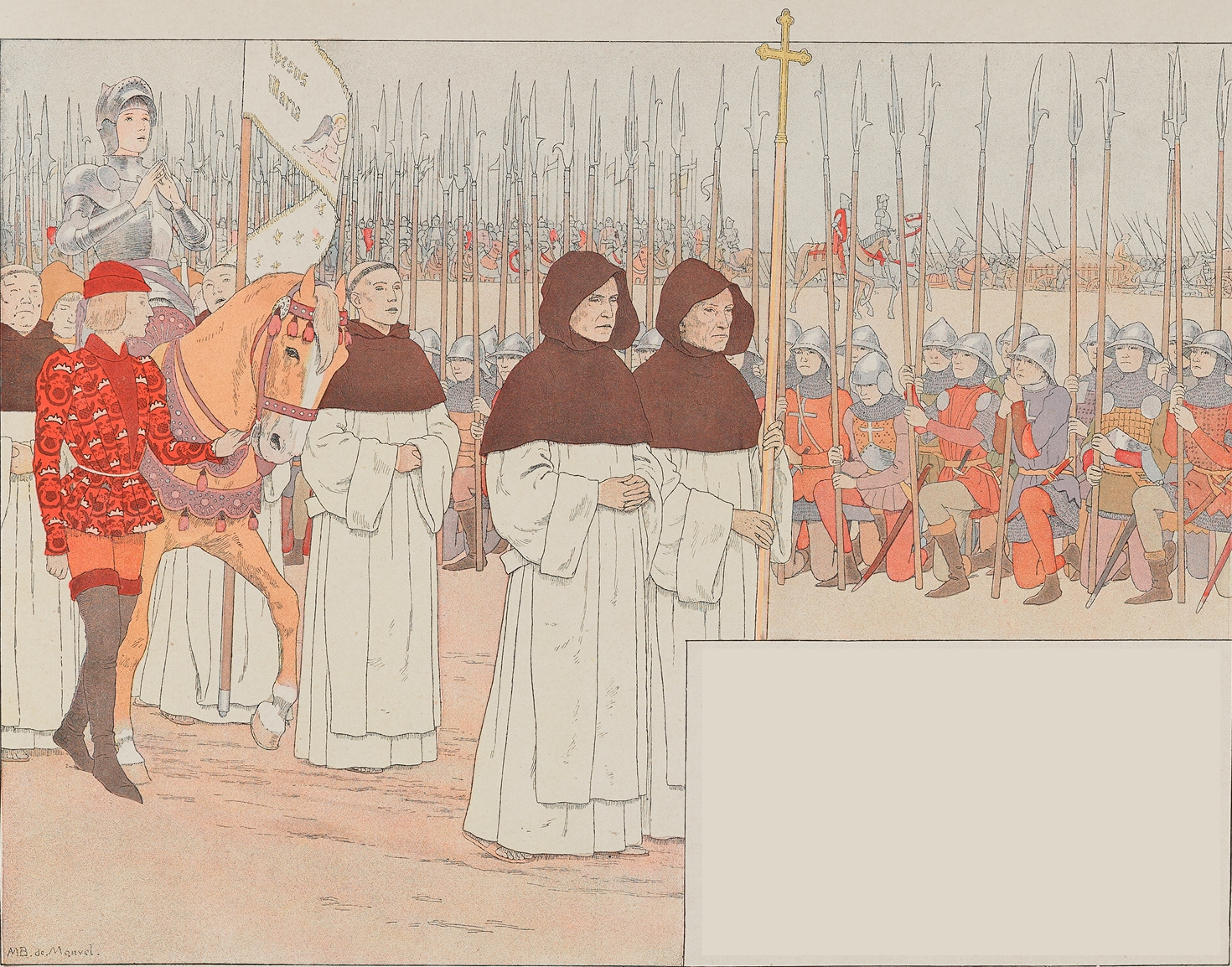

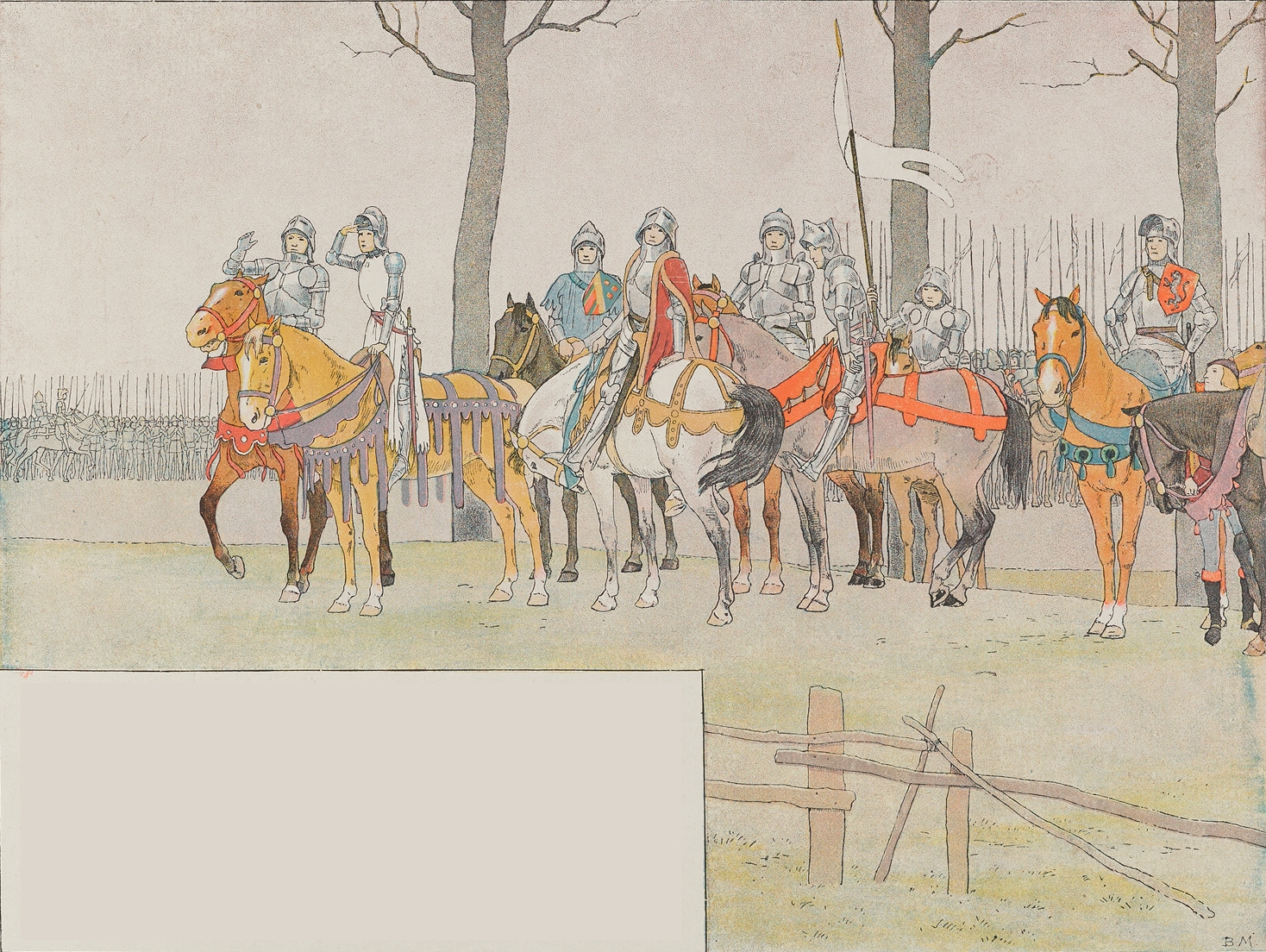

The troops gathered in Blois. Joan arrived there followed by the Duke of Alençon, Marshal de Boussac, the Lord of Rais, La Hire, and Xaintrailles.

On her white standard, she had the image of God and the names of Jesus and Maria embroidered. She advised her soldiers to sort out their consciences and confess before going out to fight. On Thursday, April 28, the small army set out. Joan led the way, her standard in the wind, to the song of “Veni, Creator”.

She wanted to march straight towards Orléans; the leaders thought it more prudent to go via the left bank of the Loire.

Scene 10

The army and the convoy arrived in front of Chécy, two leagues above Orléans.

It was a matter of crossing the Loire; the boats were missing. Joan was transported to the other bank with part of her escort and the convoy of supplies. The rest of the troops had to return to Blois, to return to Orléans via the right bank of the Loire, via Beauce.

Scene 11

Joan had said to Dunois, who had come to meet her:

"I bring you the best help, the help of the King of Heaven; it does not come from me, but from God himself, who, at the request of Saint Louis and Charlemagne, had pity on the city of Orléans."

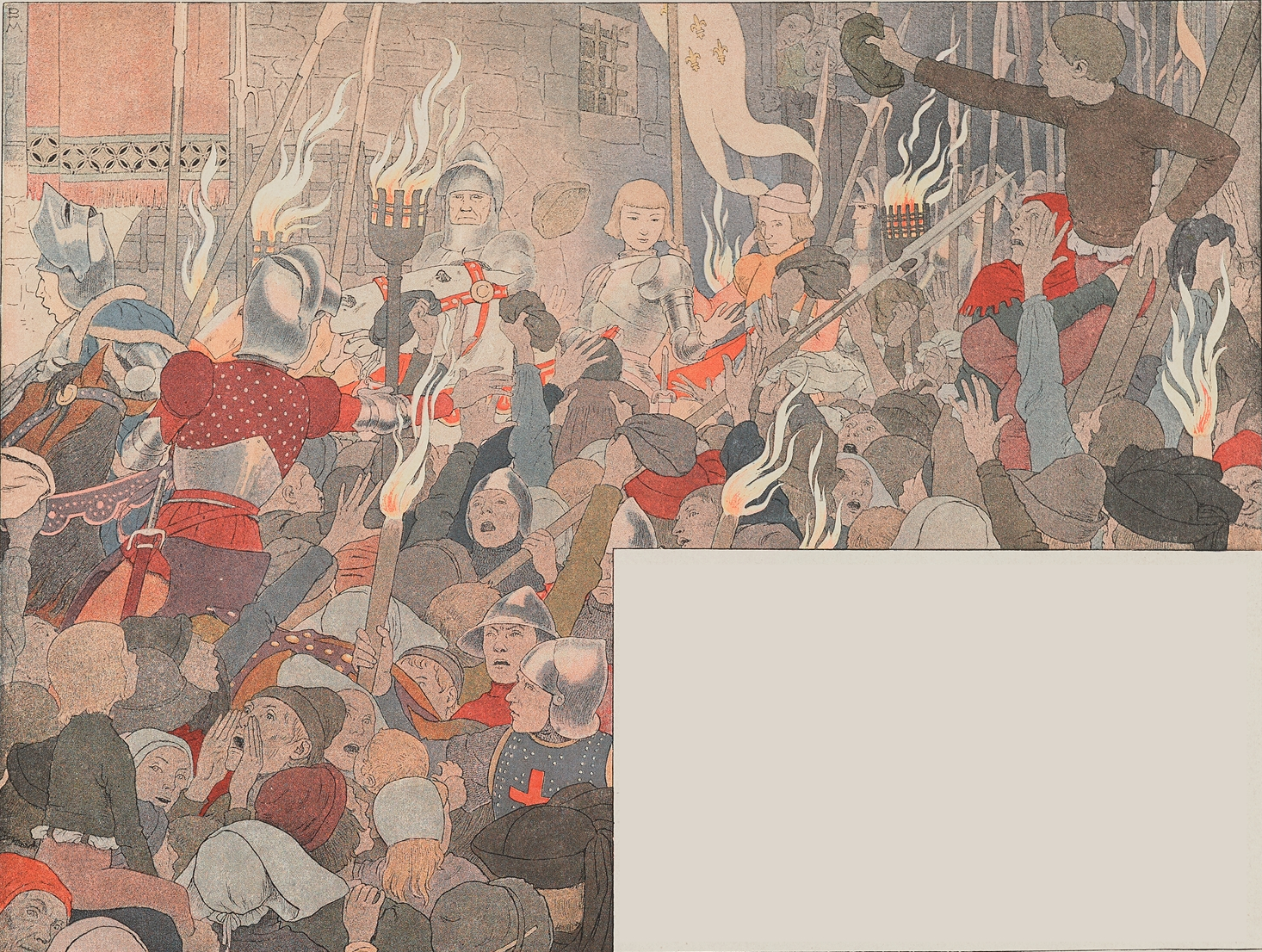

At eight o'clock in the evening, Joan entered Orléans. The people rushed to meet her. By the light of the torches, she crossed the town in the middle of a crowd so dense that she had difficulty making her way. Everyone, men, women, and children, wanted to approach her or at least touch her horse, showing "such great joy as if they had seen God descend among them."

"They felt, says the headquarters diary, comforted and as if relieved by the divine virtue of this simple girl."

Joan spoke to them gently, promising to deliver them.

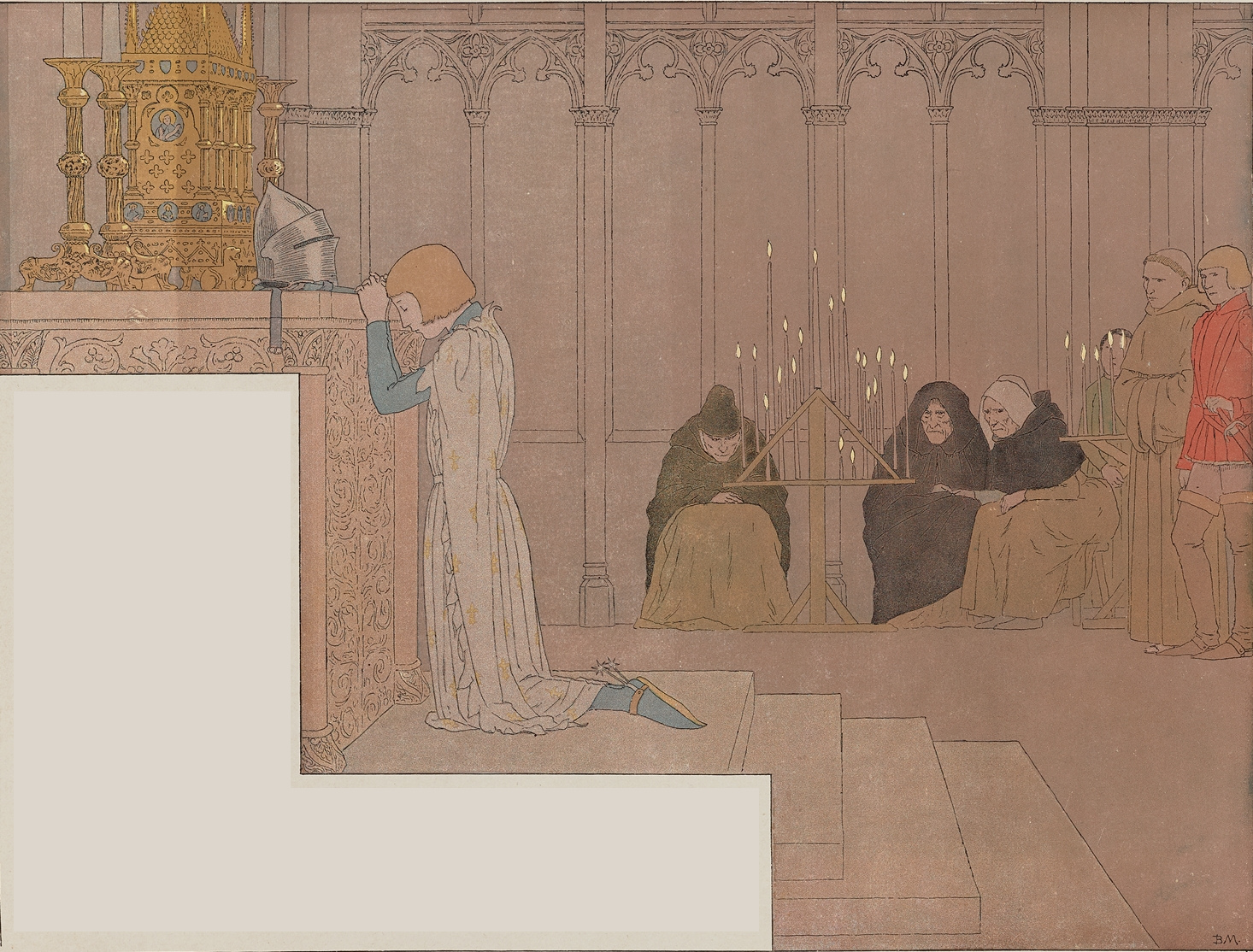

Scene 12

She asked to be taken to a church, wanting above all to give thanks to God.

As an old man said to Joan, speaking of the English:

“My daughter, they are strong and well fortified, and it will be a great thing to put them out,” she replied: “There is nothing impossible to the power of God.”

And, in fact, her confidence won over everyone around her. The Orleanians, so fearful and discouraged the day before, now fanaticized by her presence, wanted to throw themselves on the enemy and remove their bastilles. Dunois, fearing failure, decided that they would wait for the arrival of the relief army to begin the attack. In the meantime, Joan summoned the English to withdraw and return to their country. They responded with insults.

Scene 13

However, we received no news from Blois. Dunois, worried, left to hasten the arrival of help. It was time. The Archbishop of Reims, Regnault de Chartres, Chancellor of the King, reconsidering the decisions taken, was going to send the troops back to their garrisons. Dunois obtained to take them to Orléans.

On Wednesday, May 4, in the morning, Joan, surrounded by all the clergy of the city and followed by a large part of the population, left Orléans; through the English bastilles, she advanced in a grand procession to meet the small army of Dunois, which passed under the protection of the priests and a girl, without the English daring to attack it.

Scene 14

The same day, as Joan was resting, she woke up with a start.

"Ah! My God," she cried, "the blood of our people is spilled on the ground!... It's wrong! Why wasn't I woken up? Quickly, my weapons, my horse!"

Helped by the women of the house, she quickly armed herself and, jumping into the saddle, she set off at a gallop, her standard in hand, running straight towards the Porte de Bourgogne, so fast that sparks flew from the pavement.

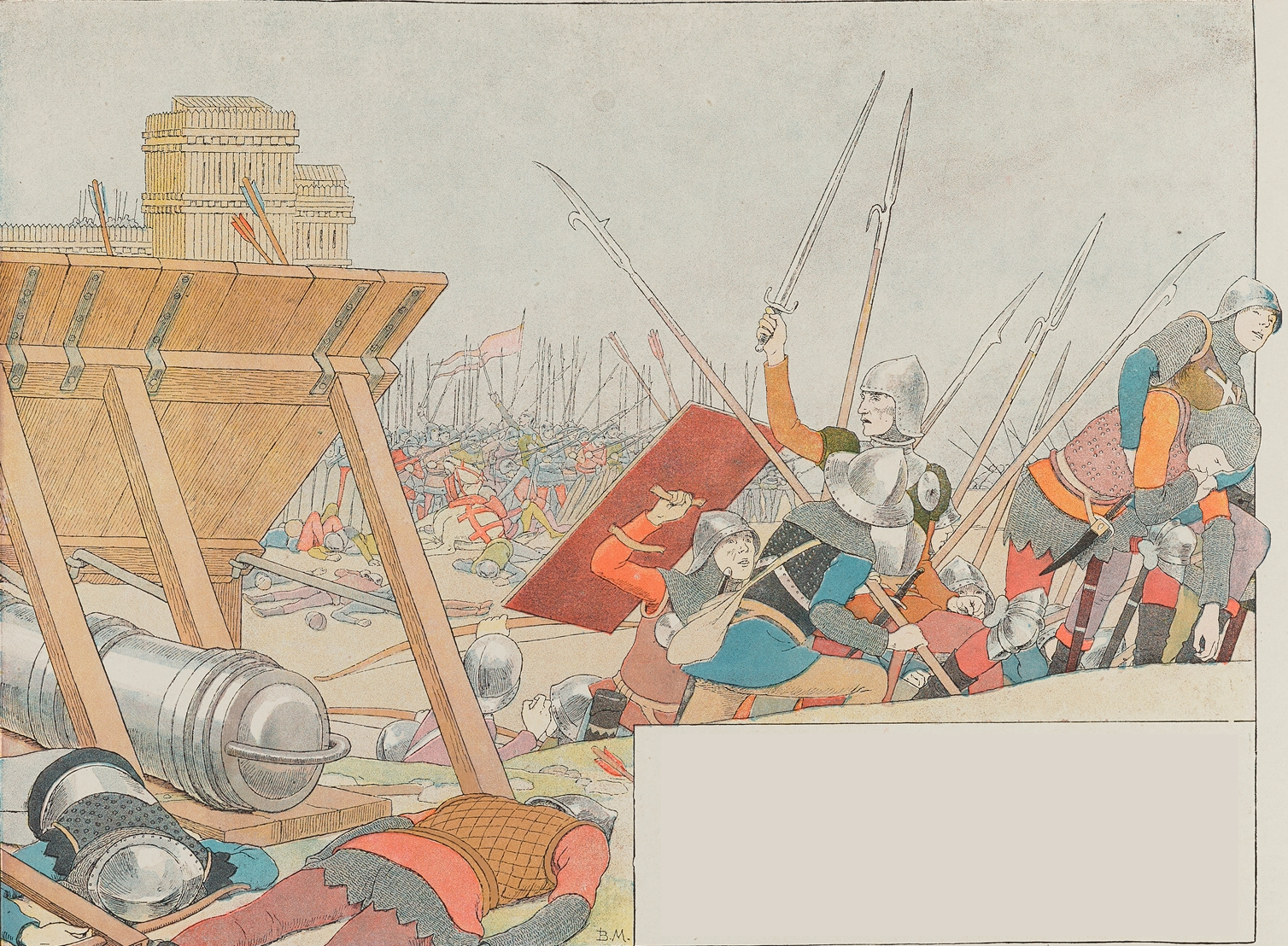

Scene 15

In fact, without warning her, the bastide of Saint-Loup had been attacked. The attack had failed; the French retreated in disorder. Joan ran to rally them, and, bringing them back to the enemy, she recommenced the assault. In vain Talbot tried to help his people. Joan, standing at the foot of the ramparts, encouraged her people. For three hours the English resisted. Despite their desperate defense, the bastide was taken.

Scene 16

Joan returned victorious to Orléans. But as, in the joy of her success, she returned towards the city, crossing the battlefield, she felt her poor heart melt with pity at the sight of the wounded and the killed, and she began to cry, thinking that they had died without confession. And she said “that she had never seen the blood of France being spilled before. Her hair stood on end.”

Scene 17

However, it was a question of deciding how this attack which had so happily begun would be continued against the English.

The chiefs, unconcerned about letting themselves be led by a country girl or sharing with her the glory of success, met in secret to discuss the plan to adopt.

Joan presented herself to the council; and as the chancellor of the Duke of Orléans sought to conceal from her the decisions that had been taken:

“Say what you have concluded and said,” she cried, indignant at these subterfuges; “I can conceal something greater!” she added:

"You have been in your counsel and I have been in mine, and believe that the counsel of God will be fulfilled and will stand firm, and that yours will perish. Get up early tomorrow morning, for I will have much to do, more than I ever had."

Scene 18

The next day, May 6, she captured the Augustinian bastille. On Saturday 7, early in the morning, the attack on the Tournelles bastille began. Joan, lowered into the ditch, was raising a ladder against the parapet, when a crossbow bolt pierced her right through between the neck and the shoulder. She tore the iron from the wound; she was then offered to charm the wound, she refused, saying "that she would rather die than do anything that was against the will of God". She confessed and prayed for a long time while her troops rested. Then giving the order to restart the assault, she threw herself into the heat of the fight, shouting to the attackers:

“It’s all yours, come in!”

The bastille was taken, and all the defenders perished. There was no longer an Englishman left on the left bank of the Loire.

Scene 19

On Sunday, the English lined up in battle on the right bank of the Loire. Joan forbade attacking them. She had an altar erected, and mass was celebrated in the presence of the assembled army. The ceremony finished, she said to those around her:

“See if the English have their faces turned towards us or their backs!” And as she was told that they were retreating in the direction of Meung:

"In the name of God, if they go, let them go; it does not please Lord God that we fight them today, you will have them another time."

Orléans, besieged for eight months, was delivered in four days.

Scene 20

The news of the deliverance of Orléans spread far and wide, attesting to all the divinity of Joan's mission.

The holy girl, avoiding the recognition of the Orléanais, returned hastily to Chinon. She wanted, taking advantage of the enthusiasm raised around her, to leave immediately for Reims, taking the King with her in order to have him crowned. The King welcomed her with great honors, but refused to follow her. He accepted the devotion of this heroic girl, but he understood that her generous efforts would in no way disturb the cowardly inertia of her royal existence.

It was decided that Joan would attack the places that the English still held on the banks of the Loire.

Scene 21

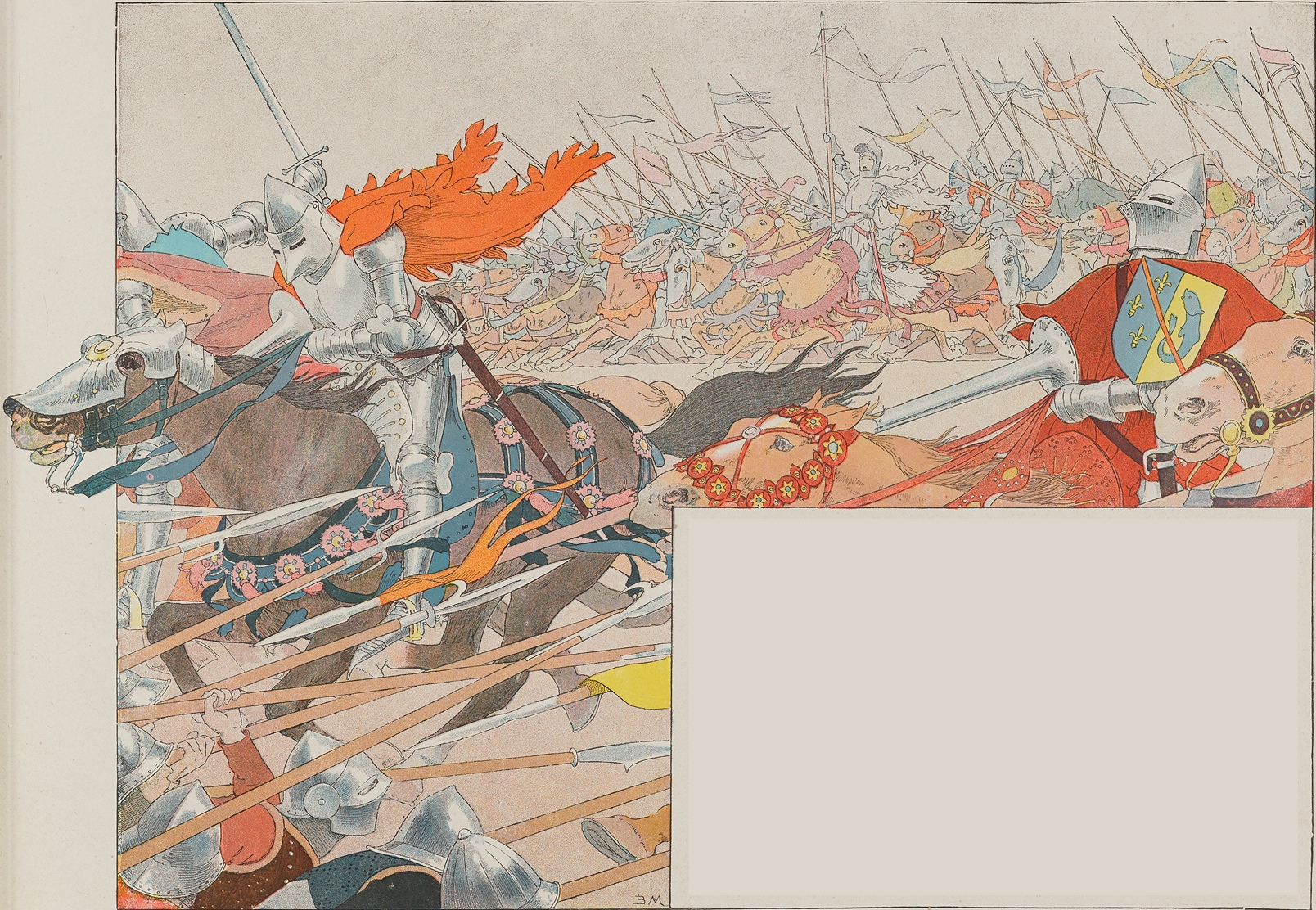

On June 11, the French occupied the suburbs of Jargeau. The next day, first thing in the morning, Joan gave the signal for combat. The Duke of Alençon wanted to delay the assault:

"Forward, kind duke, to the attack! Do not doubt, it is the hour when it pleases God; work, and God will work."

She herself climbed the ladder; she was knocked down by a stone which hit her on the head. But she got up, shouting to her people:

"Friends, up! up! Our Sire has condemned the English; they are ours at this hour; have good courage!"

The ramparts were scaled. The English, pursued as far as the town bridge, were caught and killed. Suffolk was taken prisoner.

On the 15th, the French took control of the Meung bridge;

on the 16th, they laid siege to Beaugency;

on the 17th, the city capitulated.

Scene 22

On June 18, Joan reached, near Patay, the English army led by Talbot and Fastolf.

“In the name of God we must fight them,” she said; "even if they hang by the clouds, we will have them, because God sends them to us so that we can punish them. Our kind King will have today the greatest victory that he ever had."

She wanted to go to the vanguard, but she was held back, and La Hire was charged with attacking the English to force them to turn around, in order to give the French troops time to arrive. But La Hire's attack was so impetuous that everything gave way before him. When Joan ran with her men-at-arms, the English were retreating in disorder. Their retreat became a rout.

Talbot was taken prisoner.

"You didn’t think this morning that this would happen to you," said the Duke of Alençon.

"It is the fortune of war," replied Talbot.

Scene 23

The English lost four thousand dead. Two hundred prisoners were taken from them. Only those who could pay a ransom were kept at mercy; the others were killed mercilessly.

One of them was beaten so brutally in front of Joan that she jumped from her horse to help him. She lifted the poor man's head, brought a priest to him, consoled him, and helped him die.

Her heart was as pitiful for the wounded English as for those of her party

Besides, she defied blows, and was often wounded, but never wanted to use her sword; her white standard was her only weapon.

Scene 24

The soldiers, English and Burgundians, who were garrisoning Troyes were able to leave the city with everything they owned. What they had were mainly prisoners, French people. When drawing up the capitulation, nothing had been stipulated in favor of these unfortunate people. But when the English left the city with their garroted prisoners, Joan threw herself across the road.

“In God’s name, you will not take them!” she cried.

She demanded that the prisoners be handed over to her, and that their ransom be paid by the King.

Scene 25

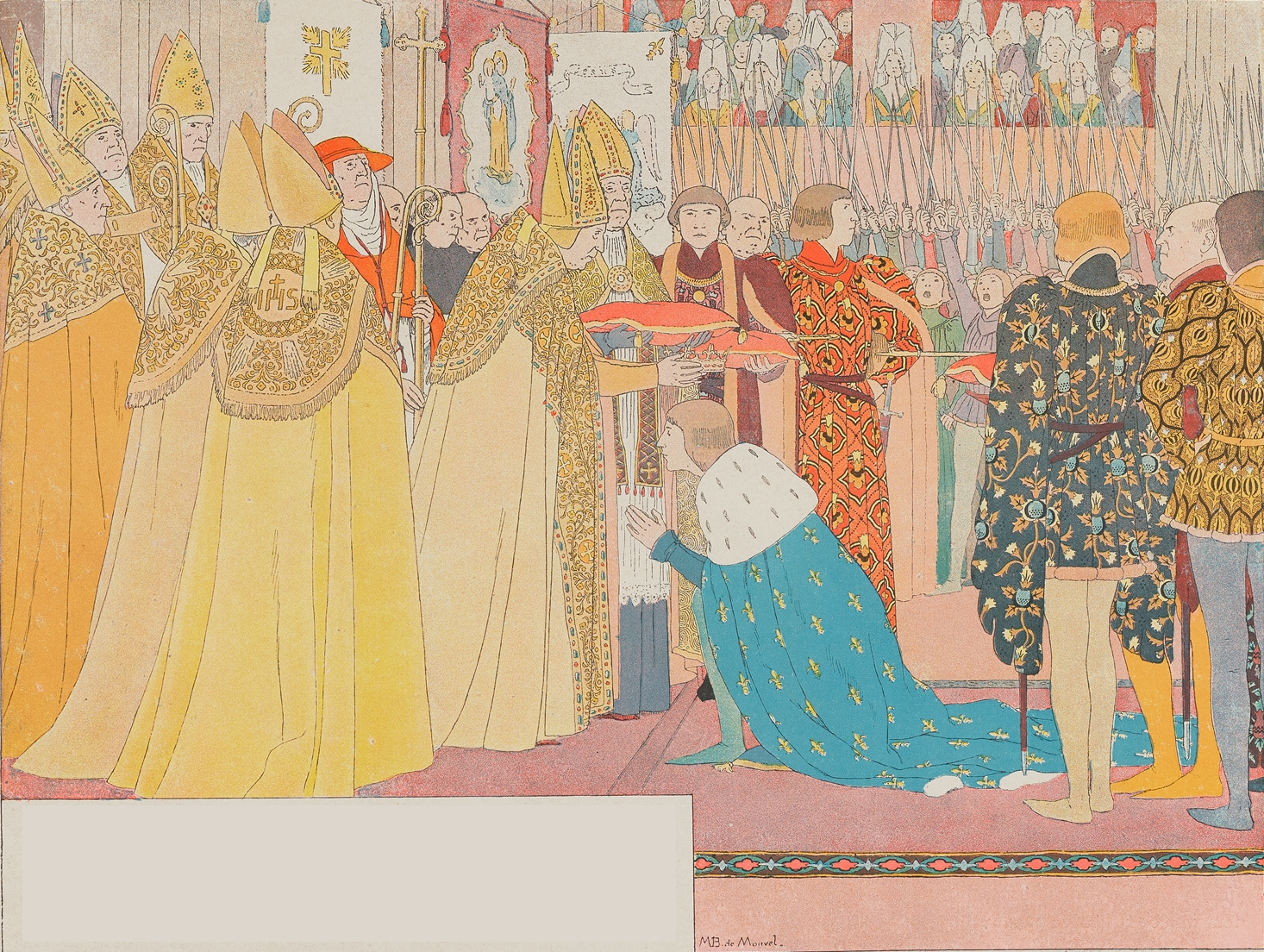

On July 16, the King entered the city of Reims at the head of his troops. The next day, the coronation ceremony took place in the cathedral, amid a great concourse of lords and people. Joan stood behind the King, her standard in her hand;

"This standard had suffered, it was right that it should be in the spotlight."

Scene 26

When Charles VII had received the sacred anointing and the crown from the archbishop, Regnault of Chartres, Joan threw herself at his feet, kissing his knees and weeping hot tears.

“O kind Sire,” she said, “now is fulfilled the pleasure of God who wanted me to bring you to your city of Reims to receive your holy coronation, showing that you are true king, and that the kingdom of France must belong to you !”

“All those who saw it at that moment,” says the old chronicle, “believed better than ever that it was something from God.”

“O good and devout people,” cried the holy girl, seeing the enthusiasm of the crowd around the King, “if I must die, I would be very happy if they buried me here!”

Scene 27

There was nothing like the eagerness of the people to touch Joan. It was about who would kiss her hands or her clothes, who would touch her. The little children were presented to her so that she could bless them, the rosaries, the holy images so that she could sanctify them by touching them with her hand. And the humble girl gracefully rejected these signs of adoration, gently joking with the poor people about their credulity in her power. But she asked on what day and at what time the children of the poor received communion, to go and commune with them.

Her pity was for all those who suffered, but her tenderness was all for the small and humble. She felt like their sister, knowing that she was born to one of them. When later she was criticized for having tolerated this adoration of the crowd, Joan will simply respond:

"Many people saw me willingly, and they kissed my hands without my permission, but the poor people came willingly to me because I did not displease them."

Scene 28

After the coronation of Reims, Joan wanted to move strongly towards Paris and retake the capital of the kingdom. The King's indecision gave the English time to make their defense preparations. The assault was repulsed; Joan was wounded by a crossbow bolt to the thigh.

She had to be taken by force from the foot of the ramparts to force her to stop the fight. The next day, the King opposed the recommencement of the attack; Joan, however, was responsible for the lack of success.

For quite a long time Charles had been dragged along the roads; he was impatient to resume his indolent life in his castles of Touraine.

Scene 29

This retreat imposed by the cowardice of Charles VII and the jealousy of the courtiers was a terrible attack on Joan's prestige.

From now on, in everyone's eyes, she ceased to be invincible.

The holy girl seems to have understood this, because, before leaving Paris, she went to place as an offering, on the altar of Saint-Denis, her hitherto victorious weapons. She prayed for a long time. Perhaps at that moment she had a presentiment that her glorious mission was over, and that painful trials were ahead for her. Nevertheless, she submitted and, with death in her soul, followed the King to Gien. The army was disbanded. The people of the court thought that we had fought enough. It was important, moreover, for their jealousy to put an end to Joan's success.

Scene 30

But Joan could not resign herself to the inaction that they wanted to impose on her. Abandoned without help during the siege of La Charité, she understood that she now had no hope of help from Charles VII. At the end of March (1430), without taking leave of the King, she left to join the French partisans who were skirmishing against the English at Lagny.

Now, during Easter week, as she had just heard mass and taken communion in the church Saint-Jacques de Compiègne, she withdrew against a pillar of the church and began to cry. The townspeople and children were surrounding her - she said to them:

"My children and dear friends, I tell you that I have been sold and betrayed, and that soon I will be delivered to death. I beg you to pray for me, because I will never again have the power to do any service to the King and the Kingdom of France."

Scene 31

On May 23, as she was in Crespy, she learned that the town of Compiègne was closely sieged by the English and the Burgundians.

She went there with four hundred combatants and entered the city on the 24th, at daybreak. Then, taking part of the garrison with her, she attacked the Burgundians. But the English came to attack her. The French retreated.

“Don’t think about anything but shooting at them,” Joan shouted, “it’s up to you that they get unnerved!”

But Joan was carried away by the retreat of her people. Brought back under the ramparts of Compiègne, the French found the bridge raised and the portcullis lowered. However, Joan, forced into the ditches, still defended herself.

Scene 32

A troop had attacked her.

"Surrender yourself!" they shouted to her. “I have sworn and pledged my faith to someone other than you,” replied the brave girl, “and I will keep my oath!”

But in vain she resisted. Pulled by her long clothes, she was knocked from her horse and taken. From the top of the city ramparts, the Lord of Flavy, governor of Compiègne, witnessed his capture. He did nothing to help her.

Scene 33

Joan was taken to Margny amid the cries of joy of her enemies. The English and Burgundian chiefs and the Duke of Burgundy himself came running to see the witch. They found themselves face to face with an eighteen year old girl. Joan was the prisoner of John of Luxembourg, a gentleman without fortune, who only wanted to profit from her capture. The king of France made no offer to ransom the captive.

Scene 34

Joan was locked up in the Château de Beaurevoir. But knowing that the English wanted to buy her from the Lord of Luxembourg and also that the siege of Compiègne was advancing and that the city was going to succumb, one night she let herself slide from the top of the keep, using straps that broke. She fell at the foot of the wall and remained there as if dead.

Joan, however, recovers from her fall. A crueler end was in store for her.

At the end of November, she was handed over to the English for a sum of ten thousand tournois pounds.

Scene 35

Locked in the prison of Rouen Castle, she was guarded day and night by soldiers, from whom she had to endure insults and even brutality, her chains not allowing her to defend herself.

Meanwhile, a tribunal, at the discretion of the English party and chaired by Cauchon, bishop of Beauvais, was investigating her trial. To the insidious questions of her judges, the poor and holy girl, without support and without advice, could only oppose the righteousness and simplicity of her heart, only the purity of her intentions.

“I come from God,” she said; “I have no use here; send me back to God from whom I came.”

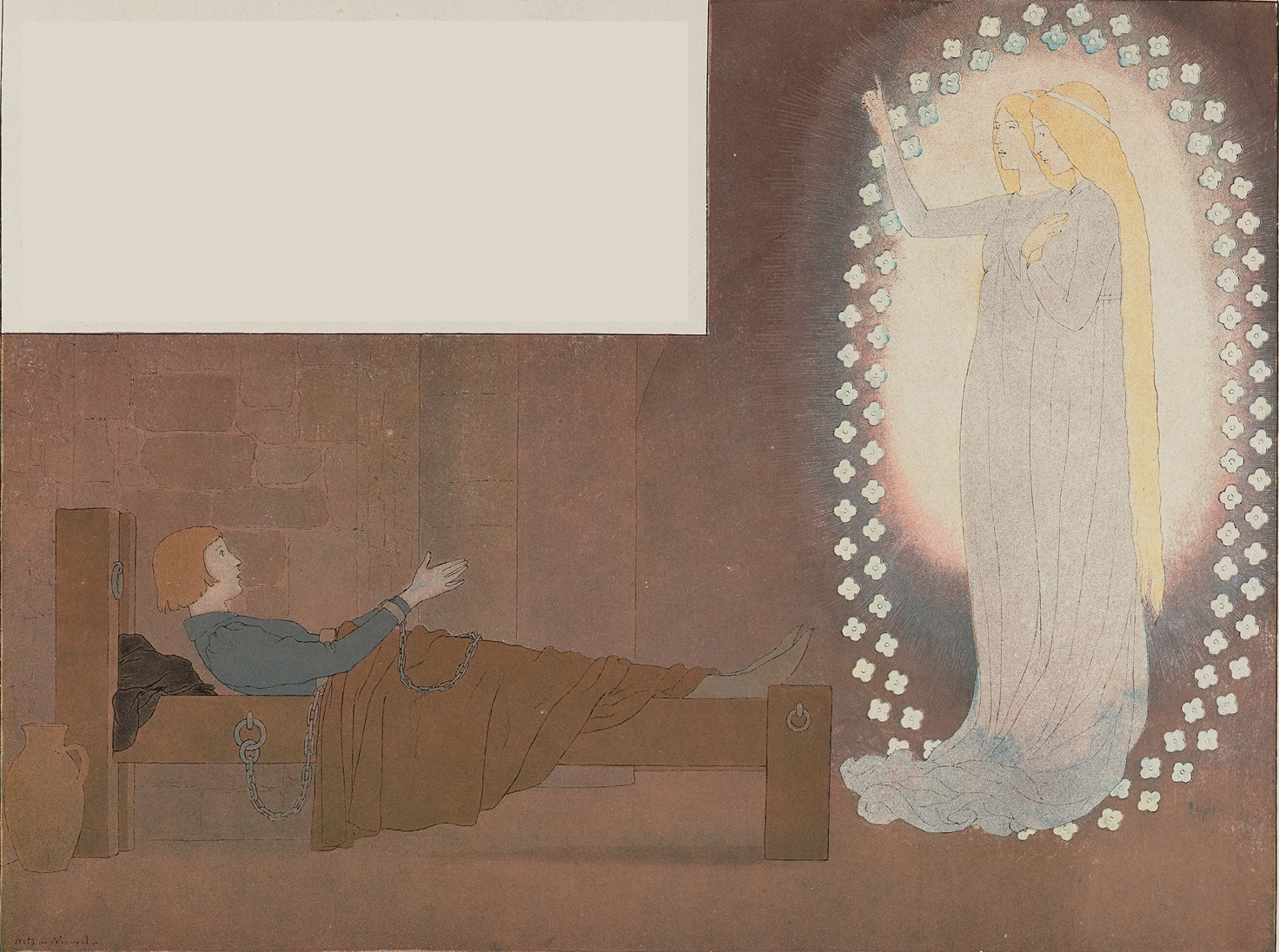

Scene 36

However, there remained one help for her: that of her saints. They alone had not abandoned her. Joan always received advice from her celestial voices; Saint Marguerite and Saint Catherine appeared to her in the silence of the night, comforting her with good words. And as Bishop Cauchon asked Joan what they said to her:

“They woke me up,” she replied, “I folded my hands and asked them to give me advice; they said to me: ‘Ask Our Lord.’”

“And what else did they say?”

“To answer you boldly.”

And as the bishop pressed her with questions:

"I can't say everything; I'm more afraid of saying something that displeases them than I am of not responding to you."

Scene 37

One day, Stafford and Warwick came to see her with Jean de Luxembourg. And as he, mockingly, told her that he was coming to buy her back if she promised not to arm herself against England again:

“In the name of God,” she replied, “you are making fun of me, because I know very well that you have neither the will nor the power; I know very well that the English will put me to death, believing, after my death, to gain the kingdom of France; but even if they were a hundred thousand more, they would not have the kingdom."

Furious, the Earl of Stafford threw himself at her.

He would have killed her without the intervention of the assistants.

Scene 38

Joan, treated as a heretic, was deprived of the aid of religion. The sacraments were forbidden to her.

Returning from the interrogation and passing with her escort in front of a chapel whose door was closed, she asked the monk who accompanied her if the body of Jesus Christ was there, requesting that she be allowed to kneel for a moment in front of the door to pray. Which she did. Now, Cauchon, having known this, threatened the monk with the most rigorous punishments if such a thing happened again.

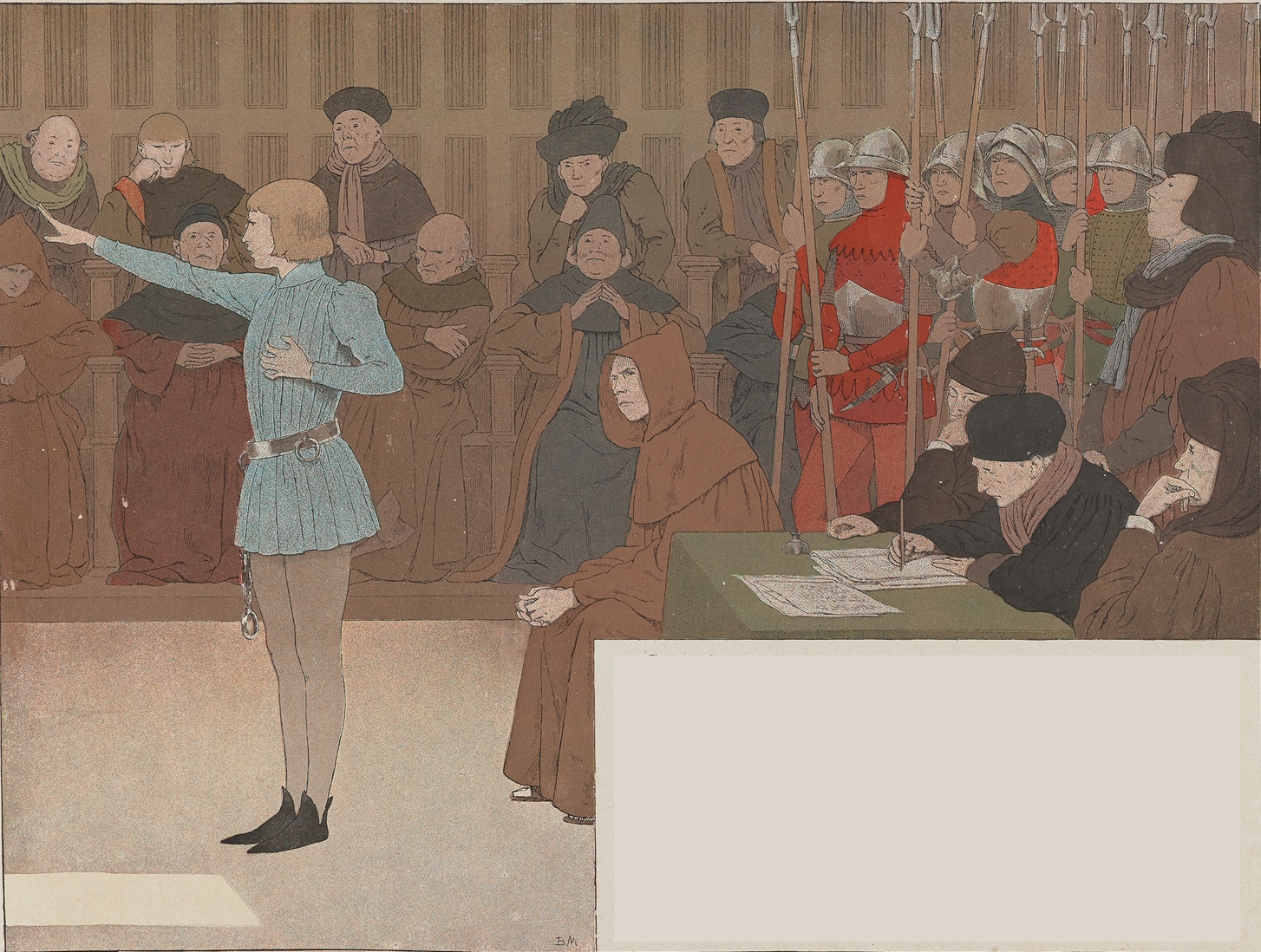

Scene 39

However, the trial moved too slowly for the English.

“Judges, you don’t earn your money!” they shouted to the members of the court.

“I have come to the King of France,” said Joan, “from God, from the Virgin Mary, the saints and the victorious Church above; to that Church I submit myself, my works, what I have done or to do. You say that you are my judges, be careful about what you do, because truly I am sent from God and you are putting yourself in great danger!”

The holy heroine was condemned, as a heretic, relapse, apostate, and idolater, to be burned alive on the Place du Vieux-Marché in Rouen.

“Bishop, I die because of you!” she said, addressing Cauchon.

Scene 40

On May 30, Joan confessed and received communion. Then she was taken to the place of execution. When she was at the foot of the scaffold, she knelt, invoking God, the Virgin, and the Saints; then, turning to the bishop, to the judges, to her enemies, she devoutly begged them to have masses said for her soul. She climbed on the stake, asked for a cross, and died in the flames while pronouncing the name of Jesus. Everyone was crying, the executioners themselves and the judges.

“We are lost, we have burned a saint!” cried the English as they dispersed.

Outro

Christ, forgive Rouen. They don't know what they're doing...

Jesus, Jesus, why have you forgotten me?

Lord, into your hand, I commend my spirit.

O JOAN, WITHOUT SEPULCHER AND WITHOUT PORTRAIT, YOU WHO KNEW THAT THE TOMB OF HEROES IS THE HEART OF THE LIVING... - André MALRAUX

ONLY PROVABLE VOLUNTEERS CAN RAISE JOAN AND OTHER HEROES BACK FROM THEIR GRAVES - Anon